Putin delivered on his threat to use natural gas as a weapon against Europe. The EU missed the chance to hit the table with its fist and cut the imports of Russian energy commodities altogether before Putin started his blackmailing. The lack of a shared strategic perspective prevents some European countries from realizing that weaning off fossils means not only fighting the climate change, but also fighting the Russian petrostate. Putin knows that and is readily exploiting the fault lines among European countries to his advantage. One factor behind the so-far failed military invasion was Putin’s misreading of the tensions in the West. The fading public interest in the war and rising energy prices may prove him right. The EU should emerge from this crisis with a new strength – Energy Security Union and European Community of Renewables – rather than letting Putin play into its weaknesses.

In the aftermath of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Europe imposed sanctions in an attempt to stop the war through ruining Russia’s economy. As these gradually came in three baskets – financial, trade, and freezing oligarchs’ assets and imposing travel bans – the economic dimension of the war in Ukraine turned into sanction warfare. However, European countries and others opposing the Russian invasion of Ukraine have not been able to use sanctions strategically as a tool of deterrence and compellence, and go beyond sanctions’ predominantly punitive objectives. Announcing a new sanction package per week is inherently reactive, repetitive, and predictable, without communicating clearly to Moscow the conditions for their eventual termination.

Moreover, poorly devised energy sanctions appear to have arrived “too little too late”, leaving the imports of Russian natural gas, as well as nuclear fuel, intact. The European energy dependence on Russia is dangerous and exposes the Achilles heel of European strategic autonomy. Paradoxically, while European leaders contemplate whether imposing sanctions on Russian gas would be a good idea, Putin has already made his gassy menaces to switch off the pipelines.

The 21st century warfare includes the arsenal of sanctions and the ability to exploit the control – and restrict access to – the financial and technological networks. Yet the delayed effects of sanctions and the lack of a crippling blow so far, if any, raises questions about how effective sanction warfare is in influencing the outcome of war. Hard power remains central.

Fighting (with) sanctions

Despite their unprecedented scope, the Western sanction strategy has so far been unsuccessful in stopping Putin’s destruction of Ukraine for two main reasons. First, it takes time for sanctions to have a desired impact. Russia is a tough case since its semi-autarkic economy and its ruble currency proved rather resilient. Despite having half of its currency and foreign-exchange reserves frozen and most of its big banking institutions having lost access to the global payment system, Russia’s economy will suffer less than expected, with only mild recession. Its GDP will shrink by mere 6% in 2022 (in contrast to the expected 15%). The stable flow of energy exports will create billions of surplus, since the Russian imports have gone down by more than 40% since February. Its financial system has stabilized thanks to, among others, finding new markets (Russian exports to China rose by 56% year on year) and new suppliers in third countries for its imports.

Incremental economic and financial sanctions do not work against the Putin regime that impoverishes its own people. Russians have this remarkable ability to adjust and sustain any economic hardships. After the West imposed sanctions on Russian economy and Western companies started leaving Russian market, Russians are finding loopholes to get by, instead of rebelling against the war that brought this dire economic situation in the first place. Sanctions got noticed mainly by the upper 2% Russians who buy imported (and expensive) goods; the rest might have got a bit more grumpy than usual about the higher cost of some food, that’s all. Sanctions mostly target Russian oligarchs to attack their patience and low tolerance for the absence of comfort. Although inflation is high (where isn’t it these days?), the Russian market looks healthy. Thanks to high interest rates, Russians keep keeping their money in Russian banks, allowing Russian ruble to bounce back to pre-invasion levels. Although ruble crashed in early March (fell by 40% against USD), the currency is trading in a stronger rate than before Russia’s invasion. Russia has imposed capital controls and raised interest rates to 20% to protect is currency.

Crucially, though, imposing sanctions is easier on paper than monitor the compliance in real world. Humans are creative and can always find ways to circumvent sanctions. It is important to constantly patch the loopholes in compliance and monitoring capacities so that they are adequate to uncover the evaders. The cost in time and resources of monitoring and policing the compliance with sanctions would be high, since Russia’s economy is much more globally connected (than Iran and North Korea), the trade with energy commodities is opaque, and it would also have to include Chinese businesses. This also makes the secondary sanctions—penalizing third entities from other countries that trade with Russia—unlikely to make a notable difference.

It turns out, therefore, that the West failed to achieve its short-term objective of sanction warfare: to make it hard for Putin to finance his war, a liquidity and balance of payment crisis. Therefore, sanctions cannot change the war dynamic overnight as their effect on Russia’s economy will materialize only in the long term, diminishing Russia’s production capacity and technological and industrial base (such as aircraft, telecoms networks, car plants, and ultimately a brain drain of Russian talents who find it impossible to live under increasingly autocratic regime). It is likely that the sanctions will take more than a year to start to bite. By then Europeans may lose interest in war as the absence of immediate effects could appear discouraging. More attention should be paid to finding the choke points in Russian economy that rely on the global value chains, such as car manufacturing and aluminium production, and press for diligent observation of export controls.

Europe’s energy dependencies: From Russia with blood

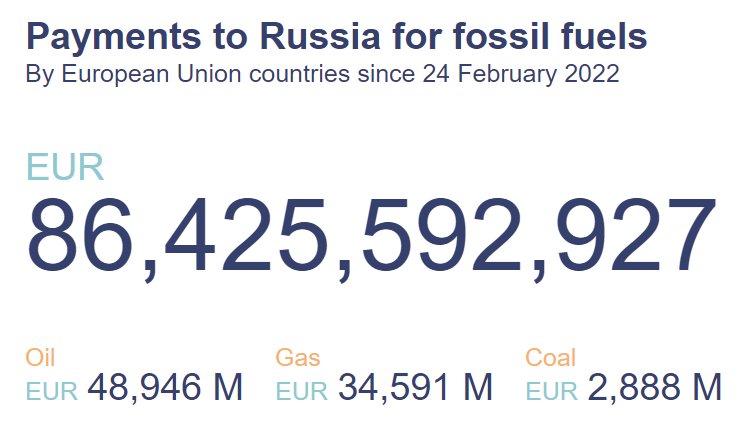

Second and perhaps more importantly, European countries do not systematically attack the main source of Putin’s revenue, energy commodities, which finance one-third of the government’s federal budget revenue. This is perplexing since Russia’s severe exposure to the export of natural resources creates a significant weakness and vulnerability typical for a petrostate. It does not come as a shock that the European energy security conundrum cannot be solved overnight. The energy security parameters in Europe have led to a situation in which the European energy sponsorship of Russia’s war in Ukraine amounts to millions of EUR per day in payments for the imports of gas and oil from Russia. Worse, European strategic energy dependence on Russian imports of hydrocarbons limits the autonomy of action in how European countries can respond to the war in Ukraine and enhance their security in a long term.

(Source: CREA, as of 27 August)

One problem lies with the fact that, not being backed by the United Nations (unlike in the Iraq case), sanctions on Russian commodities are poised to inflict lesser damage. For instance, other countries highly dependent on the energy imports, such as India, are not diversifying nor imposing sanctions on Russia. In fact, embargos and sanctions on Russia are not being supported by over 100 countries. Russians can still enjoy their holidays on the Turkish riviera. However, the lack of a wider support for sanction warfare among the international community should not discourage the Western determination to rip Russia’s energy tentacles apart.

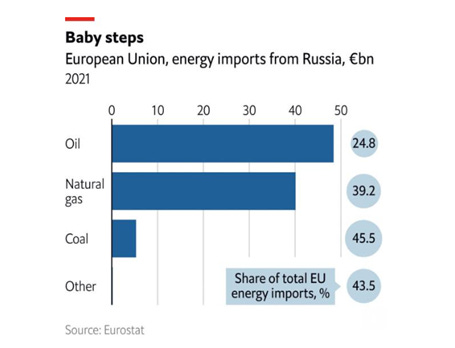

Other problem is the partial nature of energy embargos, painstakingly negotiated by European countries, on Russia. European countries struggle to rid themselves of this undesirable supplier due to the variation of the theme of energy dependence: gas and oil, and to a lesser extent coal and nuclear fuel. While coal and oil are at least partially banned, gas continues to flow to Europe largely undisrupted by diversification attempts (fake or real). The EU takes about 41% of its gas from Russia. In addition, payments in rubles further strengthens Russian currency, which in turn makes gas even more expensive.

The EU managed to phase out the import of coal from Russia within four months, although coal represents only 5% of the Russian hydrocarbon exports to the EU. The Russian coal supplies 70% of the EU’s thermal coal imports to generate electricity, and 45% of all coal imports. However, Russian coal looks less significant in comparison to oil and gas. Last year the EU spent around 5.3 billion EUR on Russian coal, out of 94,3 billion EUR on Russian energy supplies. Poland even went further and banned both Russian Belarussian coal imports.

Some European countries are considering ending the import of Russian nuclear fuel. The EU imports around 20% of natural uranium and 26% enrichment services from Russia. For instance, Slovakia and the Czech Republic import fuel for their nuclear power plants from Russia, instead from France or the United Kingdom. Combining the EU and the United States demand, Russia gets form the West only some 1 billion USD for its nuclear services. However, a Western ban would constitute a substantial blow to Russia’s nuclear conglomerate Rosatom.

The EU ban on Russian crude oil and petroleum products, as well as a on shipping insurance for oil exports from Russia, contains many exceptions and will take effect only in December. The dependence on Russian oil is strong in Germany and Italy in volume, and in Slovakia and Hungary in proportion (100%). Especially countries in the Central and Eastern Europe had long protested against this ban, which forced the EU had to revise its approach to banning Russian oil to give Hungary, Slovakia, and Czechia more time to comply until 2024. In addition, the Polish oil refinery offered to distribute oil products to all Central and Eastern European countries, since it gets only 30 percent of its oil from Russia.

The problem was mostly of a technological nature and the cost implied in transitioning away from the Russian oil. Most of oil refineries in this region cannot process but the Ural oil. In addition to energy security, this problem also raises a dilemma of a public policy order. For instance, the oil and oil product distribution services in Slovakia are provided by one private company, Slovnaft, which is owned by the Hungarian consortium Mol (which has business in Russia) and oriented mostly towards exports. It looked unwise to ask citizens to compensate a private company for its not-so-well played economic position game. While failing to modernize and diversify its production facilities so that it could process other than the Russian type of oil (despite the 2008 and 2019 crises), Slovnaft ahs been making profit through increasing oil prices. In case of Hungary, it also had a geopolitical flavour, since the Orban government’s interests are closer to Moscow than to Brussels or Kyiv. Yet if Ukraine decided to practice its European identity and join the EU oil embargo, it would stop all oil transit to EU. However, the EU dissuading oil tanker companies from transporting Russian oil to third countries in Asia would be a more effective measure. Given its slow entry into force, the EU will decrease its import of Russian oil only by 19% this year.

In contrast, the Unites States already banned imports of Russian oil, gas and coal on 8 March, thought they represents a small amount of the US energy supplies. The United States also supports imposing secondary sanctions to target those who trade with Russia. European governments have no intentions to impose secondary sanctions; they have hard times even discussing the ban on Russian gas.

Europe sanctions the war with gas money

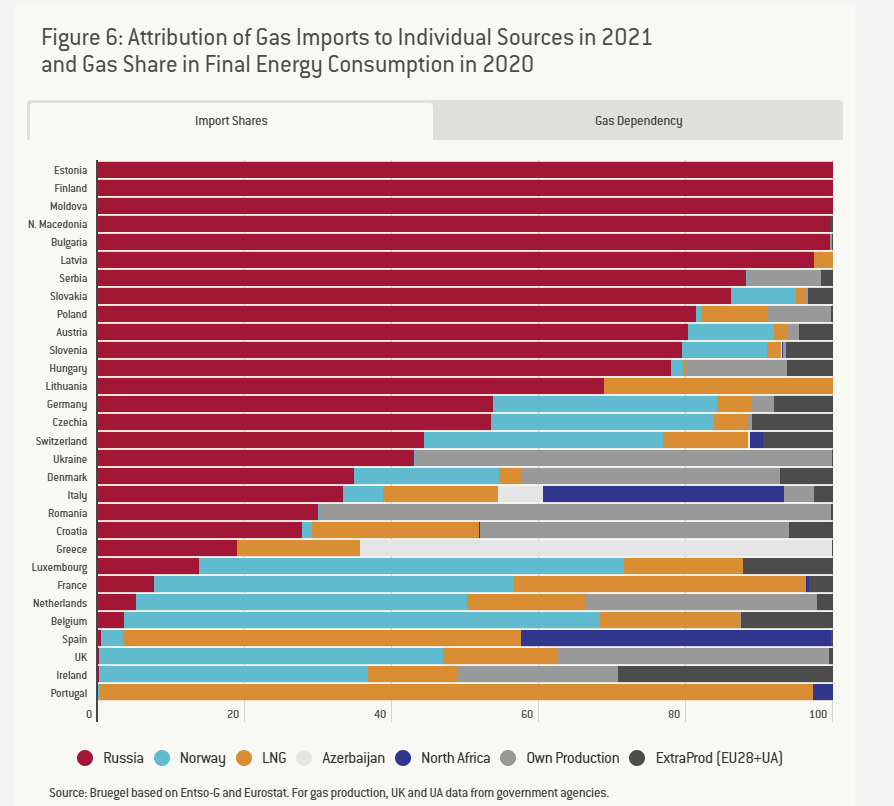

Europe’s dependence on Russian natural gas is as shameful as it is real. Half of European countries depend on Russia for more than half of their gas imports. Europe funds war it condemns. This is ethically incongruent, stinking either of cognitive dissonance or economic hypocrisy.

Sadly, it is the Russian President, not the European governments, who started to decrease the gas supplies to Europe. Putin delivered on his threat and stopped gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria because they refused to obey the Russian demand to pay in rubles (all countries that Putin labeled as unfriendly are required to pay all invoices in rubles). There are some 150 European state-owned and private entities that trade Russian gas and oil, and some are seriously considering opening (or already opened) their ruble account at Gazprom bank. In contrast, Lithuania became the first EU country to stop importing Russian gas, followed by Estonia by the end of 2022.

Trying to choke the support of Ukraine in Europe, Putin has also been playing with the volumes of gas delivered via Nord Stream. It currently runs at 20% of its usual capacity due to “maintenance closures”, endangering European gas reserves for this winter and raising prices to a record high. Saudis exercising their power over oil prices though manipulating the oil export flows does not help either.

The reasons for the continued European dependence on Russian gas are difficult to comprehend from the today’s viewpoint. In addition, the imports of gas from Russia have even increased in the past 10 years, despite Donbas and Crimea. Could it be that the EU’s % of Russian gas doubled? In 2022, the proportion of EU 27's imports of natural gas from Russia is 41%, while ten years earlier it was only 24 percent. One possible explanation is Brexit (even though the UK does not import Russian gas, it changes the pool of counties for the base calculation) and Croatia’s joining the EU in 2013.

The EU still has not imposed any sanction on gas, the most profitable energy commodity for Russia. Today the European Commission and Parliament are urging European leaders to ban the imports of Russian energy commodities, because Europe’s dependence on Russian oil and gas limits the scope of its actions. Since the dependence on gas varies, solidarity in the EU has found its limits. Calls to ban gas imports from Russia to Europe has been replaced with the instructions to European private and public entities on how to decrease is consumptions. For instance, due to Putin’s gas cutting, German authorities call for a 20% decrease in gas consumption to avoid gas shortages later this year.

Europe can do it, Germany can do it

Switching to other gas sources overnight is next to impossible since gas imports depend heavily on existing infrastructure. Natural gas needs pipelines to travel, its liquified version ships and terminals. However, Europe has more options to substitute Russian gas than Russia to replace European customers.

The most vocal opponent of full gas embargo is the EU’s largest economy. The problem is that the imported gas from Russia powers mostly German industry, not only households. Germany is afraid that cutting off Russian gas would damage Germany’s economy and throw Europe into recession, since many EU countries depend on their German trading partner.

Before the war, Germany downplayed the risk of looming war in Ukraine and the threat it could pose to Europe. Berlin traditionally supported close economic ties with Moscow in the spirit of “Wandel durch Handel” policy. Russia has been long viewed as important market for German industry and was profiting from imports of Russian gas even after the Russian annexation of Crimea. It is no accident that Gerhard Schröder, a long-time friend of Vladimir Putin, sits on the board of directors of Gazprom and Rosneft. After February 2022, cozying up with Russian elites stopped, Germany did suspend the Nord Stream 2 project which was supposed to supply gas to Germany from Russia. Germany failed to install change through trade in Russia. Putin is not Gorbachev.

Would embargo on Russian energy commodities weaken Europe more than hamper Russia’s economy in the long run? Several experts are developing scenarios for how the German energy system could become independent of Russian imports of hydrocarbons. Gas is clearly the most worrisome. Germany supplies around 55 percent of its natural gas consumption from Russia. Substitutes can make up for 70 percent of Russian gas import, that is making electricity from coal or nuclear power. Other have shown that the supply of natural gas to Germany could be secured in 2022 and in the winter of 2022-23 in case if both supply and demand sides undergo necessary adjustments. This includes gas deliveries from other countries, more efficient use of existing pipeline and storage infrastructure, shifting natural gas consumption in the power sector, and changing gas consumption habits in industry and in private households.

Although it is understandable that some fear the radical sanctions stopping the import of Russian gas might weaken Europe’s strongest economy, which would have repercussions on other European countries, sanction warfare will not make Germany a collateral damage. While every month Berlin pays for the import of Russian gas, oil, and coal around 1.8 bn EUR, an immediate embargo on all Russian hydrocarbons would hit the Germany economy less than the Covid-19 pandemic, around 3 percent v 4.5 percent of GDP decline in 2020. Other (more optimistic) sources estimate that Germany would lose only 0.5% of its GDP to a full energy embargo. According to the most pessimistic predictions, such as Germany’s Central Bank, the cost would be 5% of Germany’s GDP.

Germany could serve as a cautionary tale. Despite its gas consumption has stagnated over the past 20 years and the country is now using less gas in relation to its GDP than most European countries, Germany fell into the trap of depending on one single supplier – who turned out to be a toxic trade partner.

Sans strategy

The West needs to define the political end of its sanction warfare, which has become central to the war of nerves and resilience between Russia and the West. Before hitting Russia with another round of sanctions, the West needs to clearly communicate their purpose, what change of Russia’s behaviour it seeks and to which end state. Will the West keep the sanctions in place until Russia withdraws its forces? Returns all the seized territory in Ukraine, including Crimea? Agrees to ceasefire? In addition, imposing energy embargos with exemptions is more about keeping the West’s collective consciousness clear, rather than attempting at a meaningful change. Although the dependence on Russian energy commodities varies from country to country, it prevents the EU as a whole from imposing embargo that would put a blast on Russian main source of revenue.

Unfortunately, the Russian invasion of Ukraine made the European strategic dependence on Russian energy plain and European strategic autonomy ambitions hollow. Instead of musing about strategically autonomous European Defence Union, the EU could have its army of bureaucrats to focus on building a proper Common Energy Security Union to implement a European Energy Union. This Union should aim to decrease European dependences on hydrocarbons from autocracies and forge solidarity. For instance, through creating a shared reservoir for gas and oil, turn the EU into a powerful buyers' cartel and buy natural gas as a bloc. The CESP is where the EU can make a real difference for European security. The EU institutions have very real and concrete tools to enhance a full EU’s autonomy in strategic energy resources.

The war in Ukraine sounds like a last-minute opportunity for the EU to make a strategic break-free from fossil fuels and speed up the transition towards the European community of renewables, instead of the original coal and steal. Indeed, the EU is set on to fight off the Russian threat to its energy security by importing gas from elsewhere, accelerating transition towards renewables, and reducing energy consumption. Although the EU is gradually increasing the share of renewables, in 2020 it was 22 percent of consumed energy, natural gas represents a crucial energy source for the transition period towards the EU’s climate neutrality, because it is cleaner than coal and can cover shortfalls in renewables energy sources during less sunny and less windy periods. However, almost 84 percent of the natural gas consumption in the EU has to be imported.

Decreasing the EU’s dependence on the Russian gas imports would have been difficult to achieve if Germany had not announced its plan to build two terminals for liquid natural gas and push the expansion of renewables and its intention to stop importing Russian gas completely by 2024. This all sounds great, but European leaders have their electorates and do not want high heating bills to defeat their political careers. Not to mention asking comfortable Europeans to turn down their heating and change their consumption habits.

Since the strategy of incremental sanctions does not work immediately, especially when gas and oil are still flowing, European countries must step up military aid. Sadly, as the war is getting longer and uglier without any reasonable prospect for its end, the publics and governments in the West may start paying less attention to Ukraine’s fate and willingness to shape it. No large European country – Germany, France, Italy, Spain or Poland – made new pledge to supply weapons to Ukraine since July. The delivery of the already committed support continues. Yet the decline in military assistance does not inspire confidence in Ukraine’s counter-offensive to retake Kherson. To remedy this situation, half jokingly, Washington could ask Taliban to ship to Ukraine that 1 billion USD worth military equipment the Americans left behind already one year ago after the hasty withdrawal from Afghanistan. In the meantime, Putin’s decree to increase the size of Russia’s armed forces by 10% from 1.9 to 2.04 million was a smart move to add extra 137,000 soldiers without having to officially issue a war declaration. The war of attrition is poised to savage Ukraine.

Postmortem

In the current geopolitical situation, implementing an EU-wide energy policy means not only fighting the climate change, but rather urgently fighting back Russia’s military adventurism. The EU and its market regulation guns cannot stop Russian armoured troops physically, yet the EU can create conditions to enable Russia’s defeat. One thing is not to want risk a war with Russia out of fear of nuclear escalation, another thing is to continue paying Russia for oil and gas because politicians are afraid of losing popularity due to higher electricity bills. Betting warm households against Ukrainian lives is a bad PR strategy.

The Western support to Ukraine has been insufficient. Some government officials in Europe continue their self-deception into thinking that economic sanction warfare could have the same effects as military warfare at compelling the Russian butcher. But Putin only understands brute force, as he is not a politician and strategist, but a thug and criminal formed by his secret KGB agent past. Putin practices a thug’s business model, which not only politicizes but weaponizes Russian energy exports.

The lack of Germany leadership has been frustrating to most observers of European security affairs. The reluctant stance of Germany towards Russia could have been compensated by more significant arms deliveries, yet this is another issue where Germany holds back, making procedural excuses. Germany has been slowing down European actions in terms of both sanctions and heavy weaponry. Unless Germany talks in a matter of months and years, while the war is ranging now and its battle rhythm attunes to hours and days, this German mastodon wrestling with its own inertia cannot lead European strategic ambitions, or any European defence policy efforts.

A stable flow of more weapons into Ukraine remains important. However, more potent weapons delivered more quickly can indeed frustrate the enemy, prolong the fighting, and keep the territory free from high-intensity fighting, yet they can not win the war. The cessation of violence (and ultimately, peace) could be only achieved on the diplomatic battlefield.

The very last concluding remark points to energy commodities are likely to become increasingly central to the outbreak of international conflicts. Rather unintuitively, natural gas may have been one of the main reasons for the Russian territorial offensive in Ukraine. In the 2010s, Ukraine discovered important reserves of natural gas in the east and in the Crimea region, and to a lesser extent in the west of the country as well. This could make Ukraine the largest single supplier of natural gas to Europe (replacing the second Norway) and – thanks to already existing network of pipelines – become a serious competitor on European market. Lacking technology and skills to get the gas out, Ukraine conversed with the Western energy companies Exon Mobile, Shell, and Chevron about helping them out with their gas reserves. However, as the 2014 Orange revolution made Ukraine the most dangerous existential threat to the Russian gas monopoly, Russia did not think twice and seized Crimea and its potential offshore gas reserves (and the Sevastopol military naval base). Same logic applies to Donbas. Due to insurrections and instability in the Eastern Ukraine, all western energy companies left Ukraine gas business to its faith.

Thank you for reading! This post is free and public, without borders.

If you like it, why not share it?